This dispatch is part of our Series: Hispanic Gen Z. This series is being crafted by a multidisciplinary team of 91╩ėŲĄ analysts, strategists, and behavioral scientists, including our Hispanic Inclusive Intelligence Team. The effort cites sources such as Census data, academic research, government studies, industry papers, and social media content.

ThereŌĆÖs Hispanic, Latino, Latine, and Latinx. Also Chicano, Tejano, Boricua, Afro-Latino. ThatŌĆÖs not what this article is about. There are important differences among these terms. And much discussion about which terms are ŌĆ£right.ŌĆØ But most Gen Zers use the term ŌĆ£Hispanic.ŌĆØ And navigating that term alone is super-complex.

Hispanic identity is more complicated for Gen Zers than for their Millennial and Gen X counterparts. Why? They are less likely to speak Spanish. Less likely to live in Hispanic communities. And less likely to feel physically connected to their heritage. They are also more likely to be multiracial. And more exposed to divergent narratives about their background. At the same time, they are more proud of their heritage than past generations, and more eager to maintain an authentic connection to it.

So how are they coming to terms with their identity? In typical Gen Z fashion, they are taking all the complexity in and changing up the rules. In the Gen Z reconceptualization, Hispanic identity is less about language, lineage, or other ŌĆ£checkboxes,ŌĆØ and more about what you feel, think, and do. But itŌĆÖs also an identity-in-process.

The TL;DR: (If youŌĆÖre Gen Z), you know youŌĆÖre Hispanic whenŌĆ”

- When your cultural identity is a passion project. For Hispanic Gen Zers, cultural identity is held close to the heart. ItŌĆÖs something that is affirmed, nurtured, and celebratedŌĆöand never taken for granted. Many Hispanic Gen Zers are protective of their identity, and actively seek out ways to deepen it and to share it with others. The implication: To effectively connect with Hispanic Gen Zers, itŌĆÖs therefore essential to show up in culturally relevant spaces, and offer them ways to meaningfully engage with their culture through your brand.

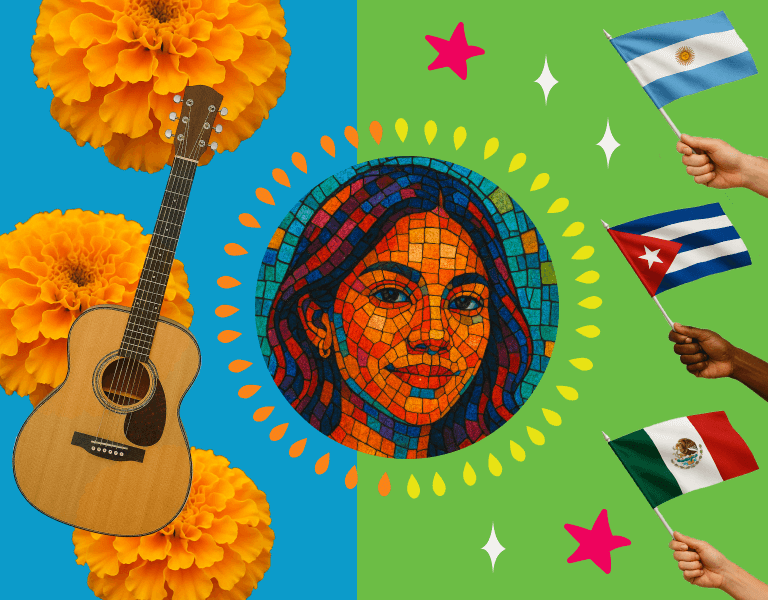

- When you actually have at least three cultural identities, and theyŌĆÖre all 100% valid. In addition to identifying as ŌĆ£Hispanic,ŌĆØ most Hispanic Gen Zers identify with at least one national identity (Cuban, Mexican, Argentine). And with their American identity. And, increasingly, with their Indigenous and/or African roots. While older generations often felt the need to ŌĆ£chooseŌĆØŌĆösometimes leaning into one identity at the expense of anotherŌĆöthere is a growing embrace of ŌĆ£mosaic identitiesŌĆØ among Gen Zers. The implication: Brands that recognize layered identities, and celebrate the interplay among them, will earn respect. ItŌĆÖs not just about honoring past heritage, but also shining a light on more fluid, future-facing expressions of what it means to be Hispanic today.

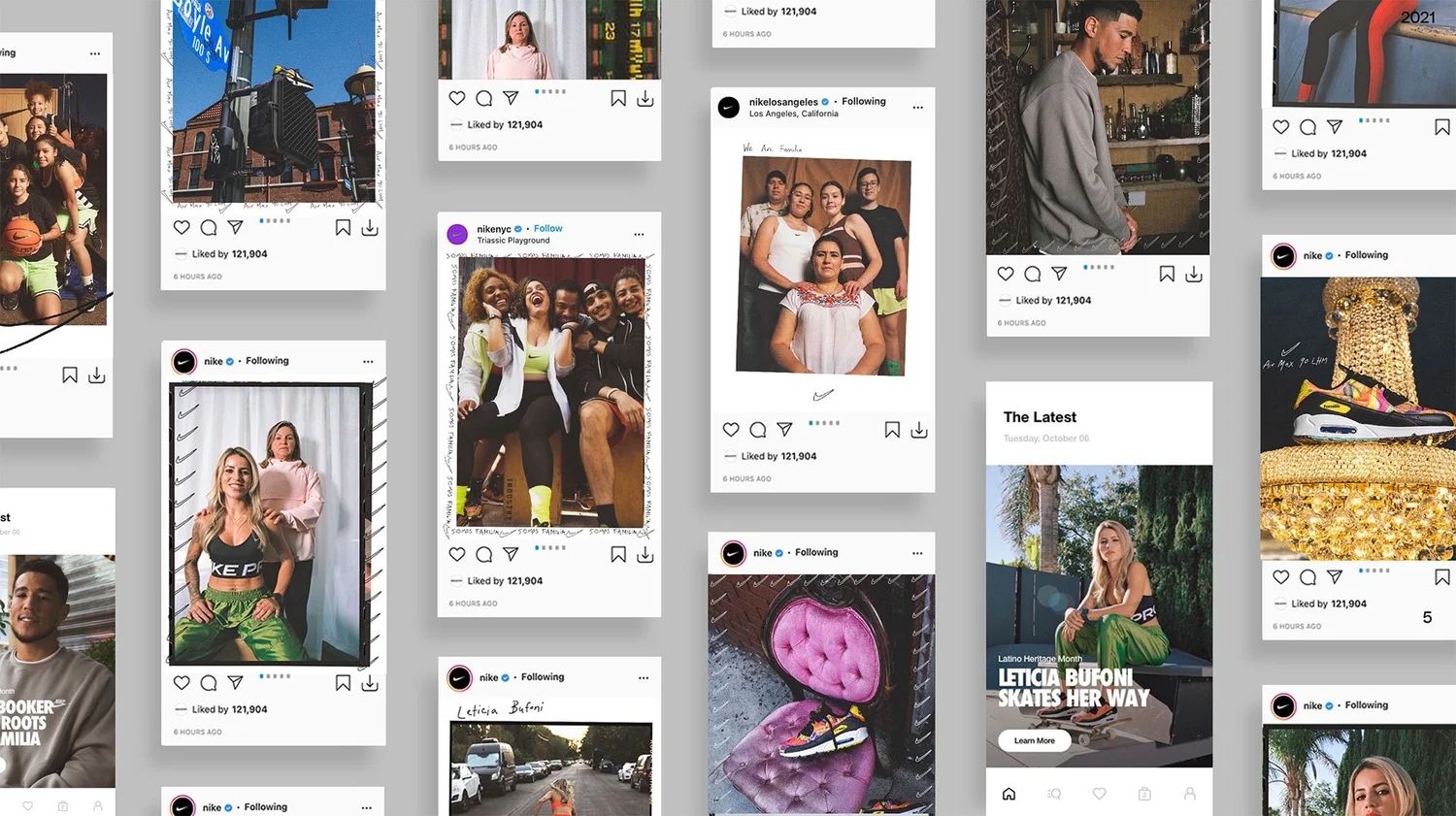

- When youŌĆÖre always ready to show up for the communityŌĆöand all-in on rallying behind authentic voices. For Hispanic Gen Zers, identity isnŌĆÖt just about what you feel and think, but also what you do. A big part of this is supporting other Hispanics both online and IRL, and helping to uplift and amplify authentic Hispanic voices. Hispanic Gen Zers are acutely aware of the way Hispanics have been sidelined by media in the pastŌĆöand of their growing influence in mainstream culture. And they are ready to play an active role in helping to shape future narratives about what it means to be Hispanic. The implication: Make community solidarity and community co-creation cornerstones of your Gen Z Hispanic strategy. ŌĆŹ

ŌĆŹ

But letŌĆÖs back upŌĆ”

LetŌĆÖs back up to a pivotal moment in the Hispanic Gen Z identity conversation. Namely, the Jenna Ortega moment. In a 2024 video for Ą■│▄│·│·╣¾▒▒╗ÕŌĆÖs ▒╩▒░∙┤ŪŌĆ»LŠ▒░ņ▒, interviewer Carolina Reynoso tells Jenna Ortega, star of NetflixŌĆÖs Wednesday, ŌĆ£Jenna, I just wanted to say, from one Latina to another, youŌĆÖre Latina enoughŌĆ”Like, youŌĆÖve opened so many doors for people like me, so you are Latina enough.ŌĆØ The now-viral clip shows Jenna thanking and hugging the interviewer, and JennaŌĆÖs Beetlejuice Beetlejuice co-star Catherine OŌĆÖHara gushing on the sidelines, ŌĆ£what a beautiful thing.ŌĆØ

Viral moment between Carolina Reynoso and Jenna Ortega

Jenna is of Mexican and Puerto Rican descent and was raised in the Coachella Valley in California. Since coming into the public eye, she has been a consistent advocate for Hispanic representation in Hollywood. But a 2023 video in which actress Anya Taylor-Joy╠²spoke Spanish and Jenna responded in English sparked comments that Jenna was a ŌĆ£fake LatinaŌĆØ (see Note 1). Not long after, Jenna herself expressed ŌĆ£shameŌĆØ at not being fluent in Spanish and a desire to connect more deeply with her roots.1

But what followed was a passionate and much more nuanced online discourse about what it means to be Hispanic and to represent Hispanic culture today. Yes, some made derisive comments and called it out as performative. But others pointed out that earlier generations often discouraged their children from learning Spanish due to assimilation pressures;2 in part because of this history, the vast majority of Hispanic Gen Zers (91%) did not grow up speaking only Spanish at home.3 Other commenters noted that Spanish is a ŌĆ£colonizer languageŌĆØ anyway; and that many Hispanics in Latin America speak Indigenous languages4 (estimates are in the tens of millions, with proportions as high as 31% in Bolivia and 49% in Paraguay).5 And many mentioned that ŌĆ£the whole Jenna Ortega conversationŌĆØ should be moved beyond ŌĆ£checkboxesŌĆØ like language: ŌĆ£Plenty of Latinos in the US donŌĆÖt speak Spanish. The real questions are: How does she identify? How has her familial and cultural background influenced her perspective? And most importantly, how does sheŌĆ”give back to the Latino community?" (see Note 2) 4ŌĆŹ

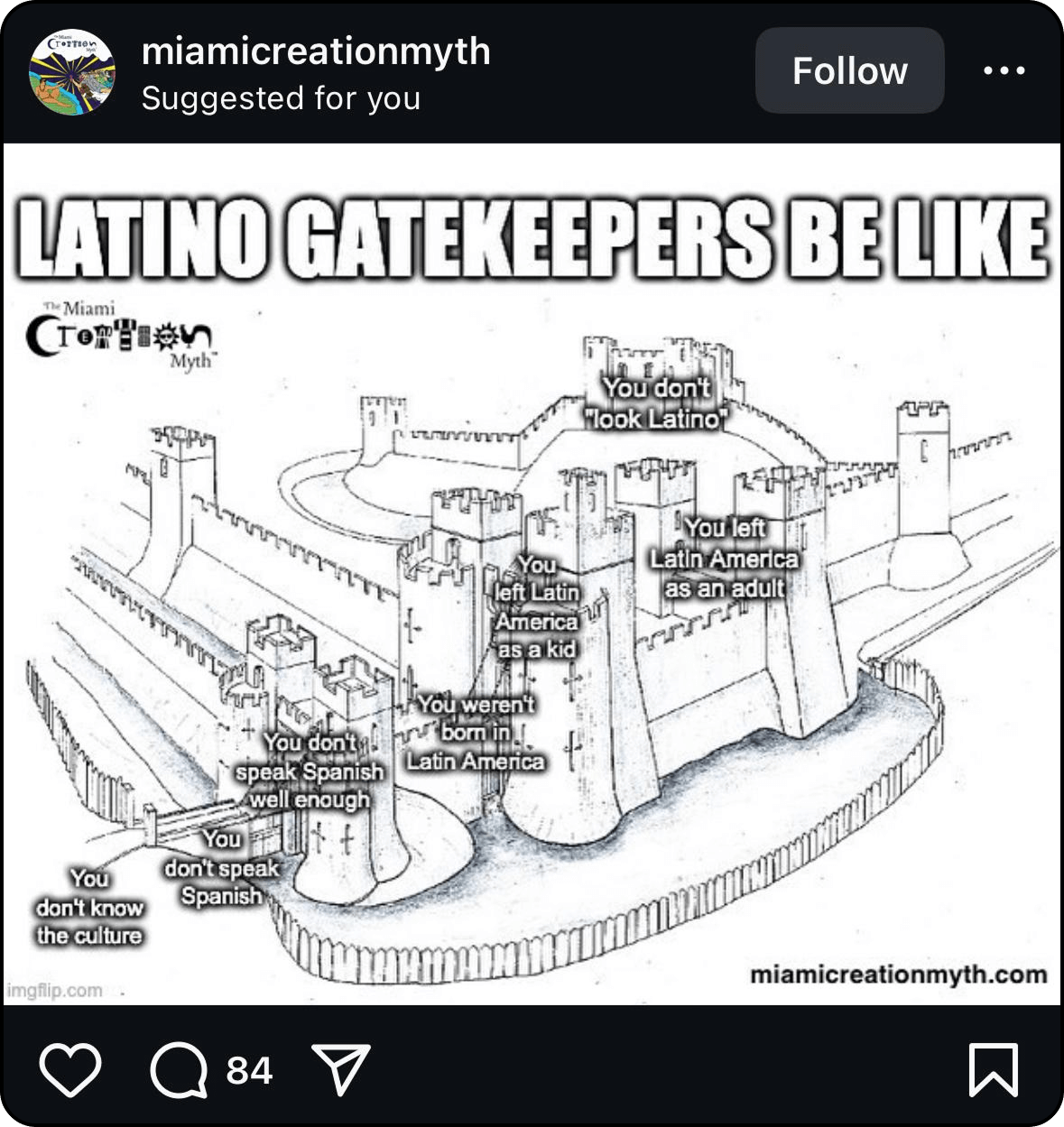

Many Hispanic Gen Zers followed this discussion with rapt attention. Most could relate. While Spanish-speaking has historically ranked as the number one ŌĆ£qualifierŌĆØ of Hispanic identity,6 only 14% of third- or higher-generation Hispanics say they can carry on a conversation in Spanish ŌĆ£very well.ŌĆØ7 (14%!). Meanwhile people have told them their whole lives that they donŌĆÖt act Hispanic enough, look Hispanic enough, or sound Hispanic enough. And these comments have come from all directions: From Non-Hispanics, from Hispanic communities within the US, and from people outside the states (on Reddit: ŌĆ£You aren't LatinoŌĆ”You didn't grow up in the society or around the cultureŌĆ”ItŌĆÖs not the sameŌĆ”You're a gringoŌĆØ).8 Perhaps most bewildering, many Hispanic Gen Zers report hearing these comments from members of their own families. For a generation that is uniquely well-educated about their heritage and enthusiastic about connecting with it, these experiences have been emotionally exhausting. So the discussion about Jenna became a flashpointŌĆösparking a real call to arms against ŌĆ£identity gatekeeping,ŌĆØ9 and helping to catalyze a new understanding of Hispanic identity. ╠²

ŌĆŹ

ŌĆŹ

- ŌĆŹ

ŌĆŹ

What is that new understanding? Language isnŌĆÖt essential. And you donŌĆÖt have to apologize for being a so-called ŌĆ£no sabo kidŌĆØ (not knowing much Spanish) (see Note 3). But how you feel about your culture matters a lot. You know youŌĆÖre Hispanic whenŌĆ” ╠²

1

When your cultural identity is a passion project.

Hispanic Gen Zers in the US are a large and incredibly diverse group. But one thing that unites them is a profound sense of pride about their cultural heritage: Identity is held close to their hearts. Compared to their Millennial counterparts, they are more likely to say they make a conscious effort to signal their Hispanic identity with their appearance (42% vs. 39%)ŌĆöthink baby hair art, papel picado tattoos, and the charro boot revivalŌĆöand they are more likely to express anxiety about ŌĆ£losingŌĆØ their connection to their Hispanic identity over time (45%vs. 41%).3 Identity is seen by this generation as a commitment and a process. Something that is affirmed, nurtured, curated, and celebratedŌĆönot simply assigned or inherited.

In line with this overarching trend, Kantar has reported that Hispanic Gen Zers engage in ŌĆ£record-high levels of cultural engagementŌĆØ in terms of media use; 68% of 18ŌĆō34-year-olds consume content related to their cultural background ŌĆ£half the time or moreŌĆØ (emphasis added), compared to 41% of those 35+.10 The implication for marketers is clear: To effectively connect with Gen Z Hispanics, it is imperative to show up in these spaces, and to offer them ways to deepen their connection with their culture through your brand.

ŌĆŹ

ŌĆŹ

Looks from Willy Chavarria's Spring/Summer 2025 collaboration with╠²Adidas Originals.

ŌĆŹ

ŌĆŹ

Among Hispanic Gen Zers, pride in culture is a huge part of what it means to be Hispanic today. But an appreciation for the complex, mosaic-like nature of Hispanic identity comes in as a close second. You know youŌĆÖre Hispanic whenŌĆ”

2

When you actually have at least three cultural identities, and theyŌĆÖre all 100% valid.

Online commenters, policymakers, and academics have debated for years about who really qualifies as Hispanic (Brazilians? Spaniards? Those with just one Hispanic grandparent?).15 But it is interesting to note that the category itself is ŌĆ£a relatively new inventionŌĆÖ (emphasis on invention).16 And something that was initially intended as a big, inclusive tent. According to UC Berkeley sociology professor G. Cristina Mora, who has written extensively on the topic,16,17╠²the term ŌĆ£HispanicŌĆØ gained mainstream traction in the 1970ŌĆÖs, when activists pushed the US Census to create a unifying category for Spanish-speaking communities. As they saw it, Mexican-Americans in the Southwest, Puerto Ricans in New York, and Cubans in Miami all shared the same challengesŌĆöpoverty, discrimination, language barriersŌĆöand by banding together under an umbrella identity, and gathering collective data on their plight, they could finally get the federal government to pay attention. The Census agreed, and engaged activists and Spanish-language media to promote the new term, so that people would use it. Documentaries, commercials, PR, and even a telethon ensued. Once added to the Census, in 1980, the wheels were in motion: Hispanics were, indeed, able to secure greater political visibility; more and more people identified with the term, which gave them ŌĆ£a feel-good sense of community;ŌĆØ and Spanish-language media were able to pitch to major advertisers like ▓č│”Č┘┤Ū▓į▓╣▒¶╗ÕŌĆÖs and Coca-Cola and thereby fund pan-ethnic programming like El Show de Cristina (ŌĆ£the Spanish-language OprahŌĆØ), continuing to reinforce and broadcast this identity. ╠²

But Hispanics have, all along, continued to identify with one or more national identities (Mexican, Dominican, Salvadoran)6 alongside their Hispanic identity. And Hispanic Gen Zers, who often have less direct experience than past generations with family countries of origin, are becoming increasingly vocal about holding space for their national identities. On TikTok, for example, Hispanic Gen Zers have embraced identity trends like saca tu bandera (bring out your flag)ŌĆöwaving their national flags while at the same time celebrating a collective Hispanic identity. The soundtrack for this trend, Gente de ZonaŌĆÖs La Gozadera, includes shout-outs to Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Honduras, Chile, Argentina, Panama, Ecuador, Uruguay, Paraguay, Costa Rica, Bolivia, Brazil, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and El Salvador (yes, 20 individual countries!). Alongside these shout-outs, lyrics celebrate the overall collective, and loosely translate as: ŌĆ£If youŌĆÖre Latino, bring out your flag;ŌĆØ ŌĆ£the world is joining the Latino party;ŌĆØ ŌĆ£nobody is bringing us down;ŌĆØ ŌĆ£turn it up.ŌĆØ ╠²

In addition to having strong attachments to their Hispanic and national identities, Hispanic Gen Zers are also fully owning their American identity. Past generations often felt the need to choose between their Hispanic identity and their American identityŌĆösometimes sacrificing one to 100% assume the other. And very often, they felt like they werenŌĆÖt succeeding at either (aka feeling ni de aqu├Ł, ni de all├ĪŌĆöneither from here nor from there). But Gen Z Hispanics are rejecting this binary view. Compared to their Millennial counterparts, they are more likely to identity with both identities.3 As Mexican-American megastar Becky G put it in a recent interview with the Associated Press: ŌĆ£A lot of the times they would tell me that I am too Mexican to be American or too American to be Mexican and that you canŌĆÖt be in the middle.╠²Why would I have to give up a part of myself to be accepted here and the other way around?ŌĆØ18 Her view represents that of many Hispanic Gen Zers. She says she╠²thinks of her identity as ŌĆ£200%,ŌĆØ and also refers to her ŌĆ£pocha powerŌĆØ (pocha being a semi-derogatory term used by Mexicans for ŌĆ£no sabo kidsŌĆØ). ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs what IŌĆÖm about: pocha power!ŌĆØ This confident embrace of both Hispanic identity and American identity is reflected in Hispanic Gen ZersŌĆÖ adoption of the phrase de aqu├Ł yde all├Ī (from here and from there), and in their rising use of Spanglish.19

ŌĆŹ

Becky G, in accepting the ŌĆ£Impact AwardŌĆØ at the 2023 Billboard Women in Music Awards, talks about feeling ni de aqu├Ł, ni de all├Ī, and embracing a 200% identity.

ŌĆŹ

And there is (at least) one more layer: Increasingly, Hispanic Gen Zers are also embracing their Indigenous and/or African roots. This shift has been fueled by the proliferation of explainer content online that unpacks the history of colonialism in Latin America, and by the increased recognition of issues like cultural erasure and Hispanic colorism by a range of Hispanic public figuresŌĆöfrom rapper Bad Bunny to congresswoman AOC. As Princess Nokia raps in her genre-defying track Brujas (Witches), ŌĆ£I'm that Blacka-Rican bruja straight out from the Yoruba / And my people come from Africa diaspora, Cuba / And you mix that Arawak, that original people / I'm that Black Native American, I vanquish all evil.ŌĆØ20 Like Becky G, who embraces her intersectional pocha power, Princess Nokia says of her Afro-Indigenous heritage: ŌĆ£I celebrate it more than anythingŌĆ” Young kids are feeling liberated with the fact that they are not just one thing that they have to personify. They can represent so much more.ŌĆØ21

Hispanic Gen Zers seem to be intuitively aware of something that science is also beginning to show: A ŌĆ£mosaic identityŌĆØ confers unique advantages: A broader worldview, greater empathy for others, and enhanced creativity.22 And while not all Hispanic Gen Zers identify as having Indigenous or African roots, letŌĆÖs not forget that many, if not most, have a Non-Hispanic parent and/or mixed-heritage parent.15 Brands that recognize Hispanic Gen ZersŌĆÖ layered identities, and celebrate the interplay among them, will earn respect. ItŌĆÖs not just about honoring past heritages, but also shining a light on more fluid and future-facing expressions of what it means to be Hispanic today.

ŌĆŹ

ŌĆŹ

ŌĆŹ

ŌĆŹ

Video from the 2022-2023 ŌĆ£Caf├® Bustelo Est├Ī Aqu├ŁŌĆØ campaign.

While not all brands are Nike, Spotify, or Caf├® Bustelo, key learnings are transferable: Allow Hispanic Gen Zers to tell their own stories; engage their communities in spreading those stories; communicate the way they doŌĆöin Spanish, English, and SpanglishŌĆöand, if you can, get a bomb soundtrack.

ŌĆŹ

ŌĆŹ

Pride in Hispanic culture and appreciation for its complexity are core to Hispanic Gen ZersŌĆÖ definition of Hispanic identity. Also core is the idea of getting behind other Hispanics. You know youŌĆÖre Hispanic whenŌĆ” ╠²

3

When youŌĆÖre always ready to show up for the communityŌĆöand all-in on rallying behind authentic voices.

An intrinsic part of any cultural identity is the notion of a common fateŌĆöthe idea that cultural and personal interests are aligned.32 And Hispanic identity is no exception. The idea is this: When one of us shines, we all shine; and when one of us needs help, we should all be sympathetic. Hispanic Gen Zers might express this idea with phrases like ŌĆ£we got you, famŌĆØ or ŌĆ£para la comunidadŌĆØ (ŌĆ£for the communityŌĆØ).

Hispanic Gen Zers on the whole share this collectivistic perspective, and they are also real about delivering on it. TheyŌĆÖll go out of their way to share╠²│”│¾Š▒▓§│Š▒╠²(gossip or insider info) that might help others level upŌĆölike putting a friend onto a scholarship opportunity or warning others about a predatory landlord. TheyŌĆÖll get behind #latinaowned small businesses and events that headline Hispanic talent. TheyŌĆÖll invest serious time in family caregivingŌĆöas well as IRL cultural celebrations, protests, and local fundraisers. And theyŌĆÖll take their support to the marketplace (according to Nielsen, Hispanics overall are 1.5x more likely to be repeat buyers when they believe a brand values their cultureŌĆöa number thatŌĆÖs likely higher among Gen Zers).33

ŌĆŹ

On TikTok, users celebrate Mar├Ła Gabriela de Far├ŁaŌĆÖs role in the recent Superman movieŌĆöelevating her individual success as a symbol of hope and resilience for Venezuela overall.

Hispanic Gen Zers are also all-in on supporting fuller and more nuanced representations of their culture in media. In HollywoodŌĆÖs telling, Hispanics still fit a certain mold: Most are Mexican; many are undocumented immigrants; men tend to be gardeners or narcos; and women are often ŌĆ£spicy Latinas.ŌĆØ According to a 2024 McKinsey study, Hollywood also still sidelines Hispanics as ŌĆ£perpetual foreigners,ŌĆØ outsiders to US culture rather than integral to it.34 Understandably, Hispanic Gen Zers think mainstream media is totally missing the plot (in a 2023 Axios/LATV study, 44% said the media doesnŌĆÖt ŌĆ£getŌĆØ them,35 and 41% said the media doesnŌĆÖt make them feel good about being a young Hispanic).36 They think there is huge upside opportunity here. ╠²

Unlike their Millennial counterparts, who largely pushed for greater numeric representation of Hispanics on-screen, Gen Zers are getting behind the call for more diverse, authentic, and overall accurate portrayals. Both tokenism and ŌĆ£Latino-coatingŌĆØ (aka superficial use of Hispanic aesthetics) are no-goŌĆÖs. Instead, they would like to see Hispanics cast more often as main characters; theyŌĆÖd like to see more Hispanic characters who are joyful, powerful, or flawed in fully human ways; theyŌĆÖd like to see the full mosaic of Hispanic identities reflected (including Afro-Latino and Indigenous identities); and theyŌĆÖd like to see more Hispanic roles that defy gender norms or are specifically written as LGBTQ+ or non-binary. TheyŌĆÖd also, of course, like to see more Hispanic creators behind the scenes (see Note 6). And they feel like the time to see these changes is right now.

Why? Because Gen Z Hispanics are super-aware of their expanding influence on mainstream culture. They are witness to the rising popularity of Latin music genres like ░∙▒▓Ą▓Ą▓╣▒│┘├│▓į (Bad Bunny, Karol G); to the mainstreaming of regional Mexican foods (horchata, chamoy-topped sour candies); to the growing adoption of Latin-inspired streetwear (lowrider aesthetics, ropa de rancho); and to the virality of Latina beauty trends (hoop earrings, lined lips). As Bad Bunny put it in a track from his album ŌĆ£Un Verano Sin T├ŁŌĆØŌĆöwhich happens to be the most-streamed album of all time, as of August 202537ŌĆöŌČ─£la capital del perreo, ahora todos quieren ser latinoŌĆØ (loosely: ░∙▒▓Ą▓Ą▓╣▒│┘├│▓į culture has taken center stage, now everyone wants to be Latino).38 To be sure, Hispanic Gen Zers are wary of cultural appropriation, ŌĆ£Latino-fishingŌĆØ (people falsely claiming Latino identity),39 and the reduction of their culture to ŌĆ£cool trends.ŌĆØ But they are also enthusiastic about riding this wave to help push forward a future cultural landscape thatŌĆÖs rich with authentic Hispanic voices.

To recap, among Hispanic Gen Zers supporting the community is the normŌĆöand seen as a better ŌĆ£litmus testŌĆØ of Hispanic identity than speaking or looking a certain way. Supporting community means not just showing up when others need help, but also getting behind authentic Hispanic voices, and helping to push new narratives into the mainstreamŌĆöin effect, co-creating future representations of what Hispanic culture is all about. ╠²

ŌĆŹ

ŌĆŹ

A promotion for the ▓č│”Č┘┤Ū▓į▓╣▒¶╗ÕŌĆÖs Spotlight Dorado initiative, featuring 2022 winner Jes├║s Celaya, who outros: ŌĆ£Because the Latinos arenŌĆÖt coming. Ya estamos aqu├«ŌĆØ (ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre already hereŌĆØ). ╠²

ŌĆŹ

ŌĆŹ

ŌĆŹ

In 2019, 91╩ėŲĄ released a research study on Gen Z entitled╠²Identity Shifters. When viewed as a whole, this was a generation defined by fluidityŌĆöGen Zers were social chameleons who adapted their identities depending on context, audience, and platform. At the time, labels were seen as limiting and quietly avoided. And identity was something to shape-shift through, not settle into. But in the years sinceŌĆöyears marked by cultural reckonings, shifting values, and rising generational visibilityŌĆöthings have changed. And when we zoom in on todayŌĆÖs Gen Z Hispanics specifically, a new picture comes into view. For this group, identity isnŌĆÖt just flexibleŌĆöitŌĆÖs intentional, layered, and carefully curated over time. They arenŌĆÖt shying away from labelsŌĆötheir own or othersŌĆÖŌĆöbut instead picking them up, turning them over, remixing them, and wearing them with pride. And, now in their early twenties, theyŌĆÖre not waiting for recognition from others; theyŌĆÖre rallying behind their communities and actively acting to push Hispanic narratives into the mainstream. Identity for this group is complex and still in flux, but itŌĆÖs also very much in action. For brands, this is the moment to stop speaking generally as fans of the culture, and start building withŌĆönot just forŌĆöa generation that knows its power and intends to use it.

╠²

ENDNOTES

NOTE 1: Still others asked, what about perfect-Spanish-speaker Anya Taylor-Joy, is she really ŌĆ£less fakeŌĆØ or ŌĆ£more representativeŌĆØ? The QueenŌĆÖs Gambit actress, who is of Argentine and European descent, identifies as ŌĆ£white Latina,ŌĆØ and does not actively advocate for Hispanic representation the way Jenna doesŌĆöthough she was once famously referred to by Variety as a ŌĆ£person of colorŌĆØ43 (wording that was retracted ŌĆ£hella quick,ŌĆØ but did not escape lengthy online debate).44 The actress Rachel Zegler, of Colombian and Polish descent, was a third player on the scene who also became ensnared in scrutiny. And in this way, the debate continued on. ╠²

NOTE 2: While not the focus of this article, it should be acknowledged that similar phenomena occur with other groups tooŌĆöfor example people may be told they are not ŌĆ£Black enoughŌĆØ or ŌĆ£really ChineseŌĆØŌĆöalthough dynamics vary significantly across groups and across contexts.

NOTE 3: The phrase is a play on words: No sabo is a clunkyŌĆöand incorrectŌĆöway to say ŌĆ£I donŌĆÖt knowŌĆØ in Spanish; saber (to know) is an irregular verb, and the correct translation is no s├®. ╠²

NOTE 4: While gender and sexual orientation are not the focus of this article, it should be noted that the designer is openly queer, and widely known for presenting unisex and gender-fluid looks, and for using gender-subversive casting and styling.

NOTE 5: Although the Adidas ├Ś Willy Chavarria collaboration was widely celebrated for its cultural pride, in August 2025 the Mexican government and Oaxacan officialsŌĆöciting lack of consent and lack of involvement of Indigenous artisansŌĆöraised concerns about cultural appropriation. Adidas and Chavarria issued swift apologies, and committed to ongoing dialogue with the affected communities. With discussions still underway, the episode serves as a reminder that even wellŌĆæintentioned, deeply authentic projects require vigilance to ensure cultural references are engaged and credited with full transparency and respect.45

NOTE 6: Not only do they say want these things, but they are also ready to put dollars behind them. In a 2025study from Code Media,46 79% of Hispanic Gen ZersŌĆöalmost 8 out of 10ŌĆösaid that they want to learn more about brands when they use imagery that they perceive as ŌĆ£culturally authentic.ŌĆØ In the same study, when exposed to visuals that were deemed authentic, Hispanic Gen Zers showed an astounding 4x increase in brand consideration. Other research has shown similar results. By supporting more authentic and textured representation of Hispanic stories, Gen Zers know that they are effectively co-creating how the world sees and understands what it means to be Hispanic. And they are optimistic that the time for change is now.

ŌĆŹ

In╠²this Series:

Dispatch #1: Who are "Gen Z╠²Hispanics?"

Dispatch #2: "The Hardest Thing I've Ever Done"

Dispatch #3: Millonario Mindset

ŌĆŹ

Note: In this report, we are looking to uncover overarching patterns. So, we will often make general observations and predictions. We recognize that we may overlook individual, subgroup, and intersectional differences in doing this, but our project is trained on broad trends. More micro trends will be important for marketers to dive into on a case-by-case basis. We also recognize that the statistics and content available to us as third-party researchers may be biased, incomplete, or otherwise flawed. To address this, weŌĆÖve sought to source information in various forms, from various places, and to gut-check and fact-check wherever possible. But the information we are working with isnŌĆÖt always perfect. Finally, we are also using the term ŌĆ£HispanicŌĆØ loosely, often interchangeably with the terms ŌĆ£LatinoŌĆØ and ŌĆ£Latine,ŌĆØ to refer to groups with Spanish-speaking heritage. ŌĆ£HispanicŌĆØ is the term that is largely preferred based on current research, though we recognize that different terms differ in meaning and nuance.

ŌĆŹ

Sources: